As promised, we’ll get into the basic data types in this tutorial. We’ll start with the integer data type and we’ll try to have an in-depth understanding of how it is implemented in computer memory. Let’s begin.

The Integer Data Type

- “int” keyword is used to declare integer type variables in C.

- Integer type data can hold only numeric values, without any decimal point and at least one-digit long.

- It can be both positive or negative. If no sign precedes the number it is assumed to be positive.

-

The size and range of int depends on the compiler we use. 16-bit and 32-bit compilers offer different sizes of int and hence different ranges.

Compiler Size Range 16-bit 2 bytes -32768 to +32767 32-bit 4 bytes -2147483648 to +2147483647 If you want a proof the data run the following code on your compiler and see what output is produced:

#include <stdio.h> #include <limits.h> int main() { printf("Size of integer is %ld bytes\n", sizeof(int)); printf("Minimum integer: %d\n", INT_MIN); printf("Maximum integer: %d\n", INT_MAX); return 0; }On my computer the output looks something like this (Yours may look a little different!) –

Size of int is 4 bytes Minimum integer: -2147483648 Maximum integer: 2147483647

- All five modifiers can be used with int to change its properties.

- Integer type data can be decimal number, octal number or hexadecimal number. We’ll concentrate on decimal numbers first.

Now we begin the real act. How are integers stored in computer memory? The numbers we use which have digits from 0 through 9 are called decimal numbers (base 10). It is called base 10 for a reason. Every number that we use in a decimal system is a sum of groups, grouped by 10. What do I mean? Let’s take an example of 4315. We have been counting numbers for so long that we immediately know this is four thousand three hundred and fifteen. We can also see that this number can be written as follows.

4315 = 4x103 + 3x102 + 1x101 + 5x100

This is the reason we call this system a base 10 or decimal system. Computers only understand what we call binary numbers (base 2) which consists of digits 1 and 0 only. Hence it is safe to assume that computers store anything we give it in form of a binary number. But how to convert a decimal number into an equivalent binary number? Most of you might know this nonetheless let’s see how we can do that.

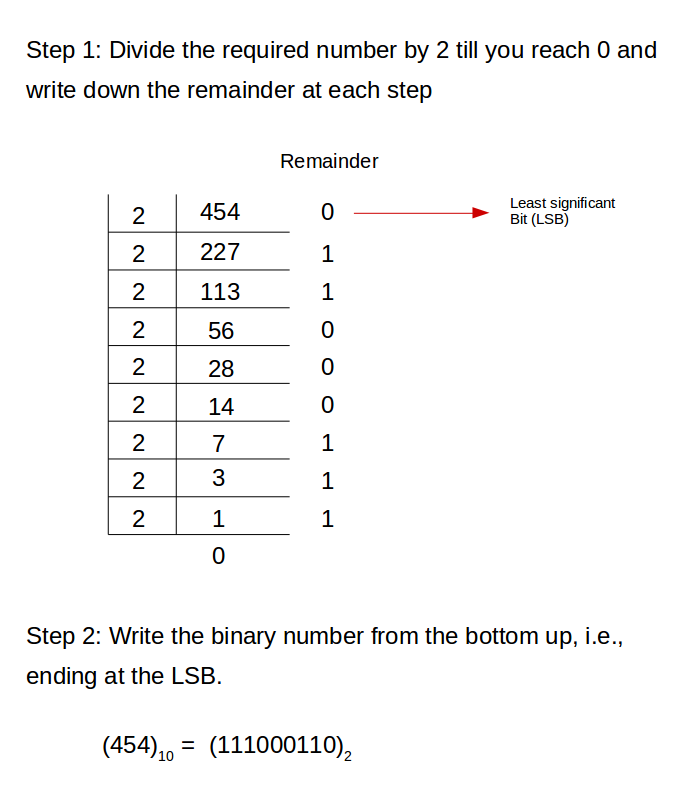

Decimal to Binary Conversion

Any decimal number can be easily converted into an equivalent binary number just by following the two simple steps:

- Keep on dividing the given number by 2 till you reach 0 and keep note of the remainder at each step.

- When division is complete, you get your binary number by writing all the remainders bottom up.

The following graphic illustrates the process with an example of 454.

I hope this makes it clear to you how we can convert a decimal number into its binary form. But, but, but! There’s one more thing. How do we get the decimal number back from here? Knowing that can help us verify if we got the correct binary number. So, let’s see that now. We know we can write 454 as

(454)10 = 4x102 + 5x101 + 4x100

and this returns to us the original number i.e., 454. We are using 10 because the number is in base 10. So why not do this exercise with the binary number that we got and see what we get? But keep in mind that it is in base 2.

(111000110)2 = 1x28 + 1x27 + 1x26 + 0x25 + 0x24 + 0x23 + 1x22 + 1x21 + 0x20

= 256 + 128 + 64 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 4 + 2 + 0

= 454

Voila! We got our number in decimal form back. So, our way was in fact correct. So now we know how to convert numbers from base 10 to base 2 and back to base 10. Well, that was pretty straight forward. But wait! What about negative numbers? How are we going to convert negative numbers? Let’s put our focus to that for a bit. We’ll see three different ways for that and see the problems associated with the first two ways and also how the last way solves these problems like a pro! Before that we need to learn the concept binary addition.

Binary addition

Though 16-bit compilers work with 16-bit (2 bytes) integers and 32-bit compilers work with 16-bit (4 bytes) integers, for the sake of convenience we’ll work with 8 bits for now. This works the same for 16 or 32 bit integers also. Binary addition simply follows the following rules:

- 0 + 0 = 0 (carry 0)

- 0 + 1 = 1 (carry 0)

- 1 + 1 = 0 (carry 1)

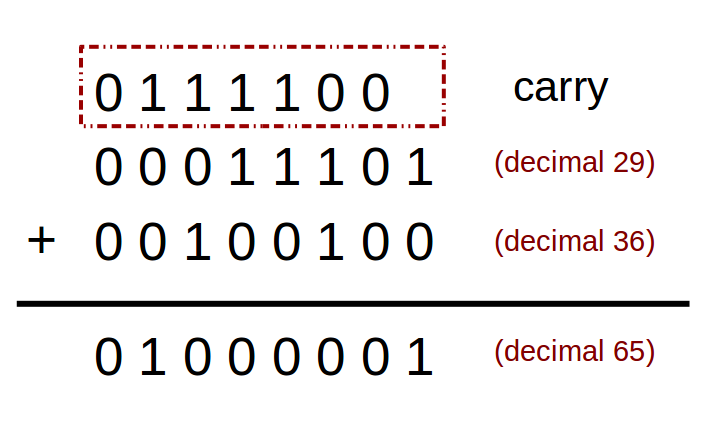

For example, let’s try to add 00011101 (decimal 29) with 00100100 (decimal 36).

This is just like normal addition. At first we add 1 with 0 to get 1 and carry 0. Then we add 0 with 0 to get 0 and carry 0. And then we add 1 with 1 and get 0 and carry 1 and so on. So we get 01000001 (decimal 65) as answer. Cool. Now, we can move our attention to negative numbers.

Representing negative numbers in binary

Let’s discuss the three common ways of representing negative binary numbers in binary number system.

Signed magnitude:

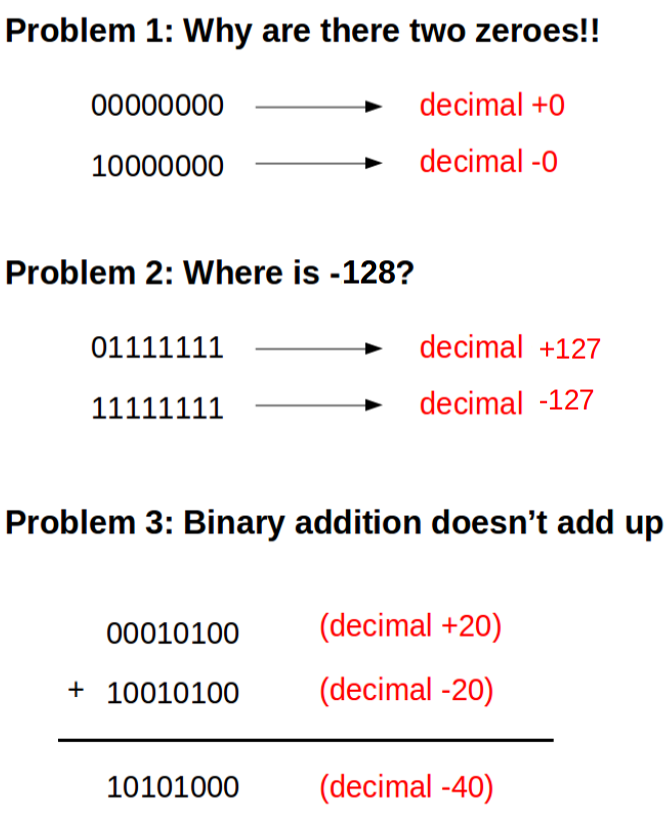

The simplest way of representing negative binary numbers is called Signed Magnitude. You use the leftmost digit or the Most Significant Bit (MSB) as a sign indication, and treat the remaining bits as if they represent an unsigned integer. The convention is that if the MSB is 0 the number is positive, if it’s 1 the number is negative. Is that it? Isn’t that so simple? NO. There are a few problems associated with that. Let’s see them.

But first, there’s just one thing to know. For 16-bit integers, the range is from -32768 (which is -215) to +32767 (which is +(215 - 1)) and for 16-bit integers, the range is from -2147483648 (which is -231) to +2147483647 (which is +(231 - 1)). In fact this will be true for 8-bit integers too. The range will be from -128 (that is -27) to +127 (that is +(27 - 1)).

These problems are certainly enough for us to discard this method of representation. The most important of all these problems is the problem of not being able to do binary arithmetic properly. Though this method of negative binary number representation was used in some very early computers, due to the difficulties posed by this method in doing binary arithmetic (which most computers do), other methods were invented.

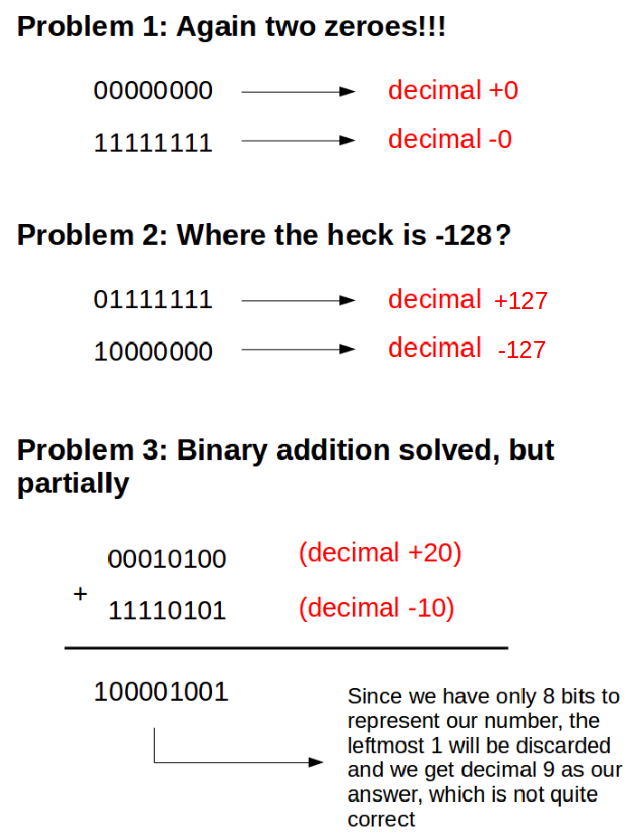

One’s complement:

One’s Complement of a binary number is another binary number which, when added to the original number, will make the result a binary number with 1’s in all bits. To obtain one’s complement you simply need to flip all the bits.

Since we are working with 8 bits,

Binary representation of decimal 20: 00010100

It’s one’s complement would be: 11101011

If we add the number and it’s one’s complement, the result would we get is 11111111 i.e., 1’s in all bits.

We can again say that the leftmost bit will determine the sign of the number. So, 11101011 will be a negative number. Which number? Since it is the one’s complement of 20, it will represent -20. Since their addition gives 11111111 i.e., decimal -0 (since the MSB is 1, we know it is a negative number; so we take its one’s complement and the value returned will be the value of our number, 0 in this case). So adding 20 and -20 in binary gives -0, which kinda makes sense. Still there are problems.

So, we are not done yet, huh! Let’s have a look at the next method and see if we can solve these problems.

Two’s complement:

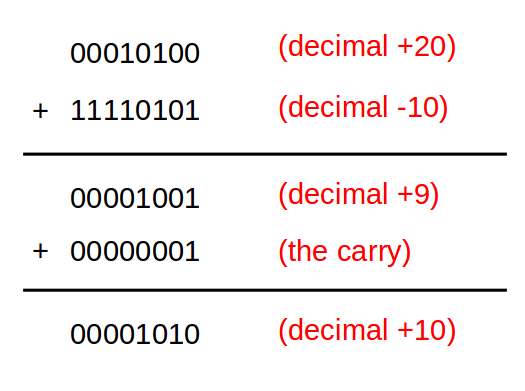

In the previous addition, if we look at the result and what the actual result ought to be, we can see that we are off by just 1 and we had to discard 1 at the leftmost bit. What if we add that carry with the remaining result? Let’s see.

And our problem is solved now! You can try that with any other problem and you’ll see the problem is no longer there.

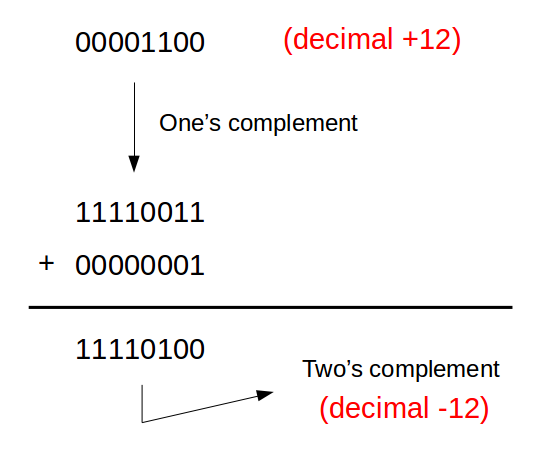

Two’s Complement of a binary number is another binary number which, when added to the original number, will make the result a binary number with 0’s in all bits. To obtain the two’s compliment of a number, we first find out its one’s compliment and then add 1 to it.

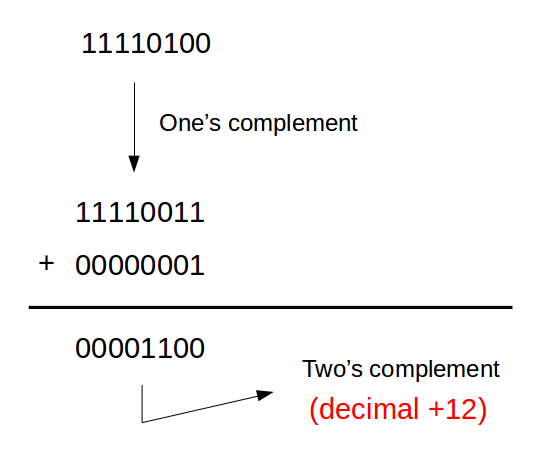

Here also, we know the sign of the number from the leftmost bit. If the leftmost bit is 0, the number is positive with the next 7 bits representing the magnitude. But if the leftmost bit is 1, we know it is negative. The magnitude can be determined by finding the magnitude of the two’s complement of the number.

Now let us try to use this process and see if we can know the decimal form of the binary number 11110100.

Hence we can say that the original number was -12 which is indeed correct if we look at the previous example and check. As is evident from all the examples, we have definitely solved our problem of binary addition (if you are not convinced try any problem on your own verify it). Now let’s see if two’s complement has helped us solve the other two problems.

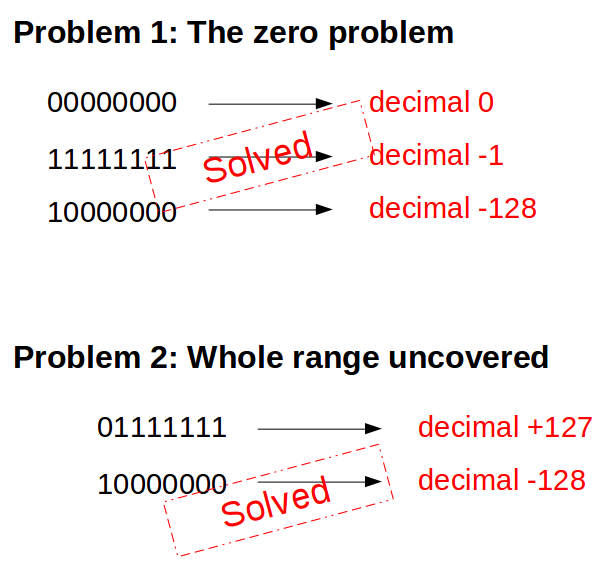

Hence, two’s complement it is! Most modern computers use this form of representation of negative binary numbers. Fianlly we can review the whole process of implementation of integers in computer’s memory just for the sake of completion.

How computers store integers

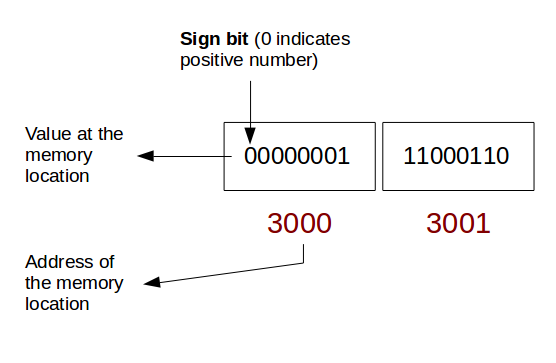

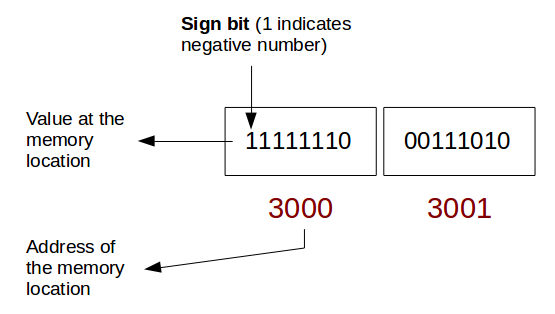

As soon as we declare a variable of type “int” a 16-bit compiler allocates two contiguous blocks of memory (one byte each). For simplicity’s sake, let’s imagine the address of the first block of memory (1 byte) is 3000. Hence the next block will bear address 3001. Convert the decimal number number into a 16-bit binary number with the leftmost bit 0 if it is a positive number or take the two’s complement of the magnitude of the number if it is a negative number. The first 8 bits will go to address 3000 while the next 8 bits will go to address 3001.

The following graphic tries to explain the process. Remember this is just a simple representation.

Similarly if we consider -454 it will look something like this.

I hope now you are clear about the idea as to how the decimal integers, both positive and negative, are represented in binary form in computer’s memory. But we are not quite done with 1’s and 0’s. In the next tutorial, we’ll take up octal and hexa-decimal integers and see how they are converted to binary and we’ll also learn the use of modifiers. We will take up floating-point data type in the one after that and see how we can represent them in binary form to get an idea of their implementation in computer’s memory. So, stay tuned!