We have covered Sequential and Decision Control Instructions so far. But are these enough? Let’s take up a situation. Suppose you were to write a program where you want to print all the numbers from 1 to 10. Sounds easy enough, right? Write 10 printf() statements and we are done. Or better yet, write all the numbers in the same printf() statement, separated by newline feed. The code can be given as follows:

/* Method 1 */

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("1\n");

printf("2\n");

printf("3\n");

printf("4\n");

printf("5\n");

printf("6\n");

printf("7\n");

printf("8\n");

printf("9\n");

printf("10\n");

return 0;

}

/* Method 2 */

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("1\n2\n3\n4\n5\n6\n7\n8\n9\n10\n");

return 0;

}

There are few problems with these ways:

- This looks way too long and damn ugly!

- The probability of doing mistake is high.

- If someone asks us to print 100000 numbers, we are doomed for life!

- If the program requires us to print n numbers, where n will be provided by the user at runtime, again we’ll be clueless!

There must be some smart way of doing this and thank Dennis Ritchie, there is! Loops are our way out of this problem. Let’s see what loops are all about.

One of the most important advantages of a computer over human beings is that it can do a task repeatedly, without getting bored and without any error. We can make our programs use this feature of computers using loop control instructions. Loops help us to use some portion of the program either a specified number of times or until a particular condition is satisfied. Loop is perhaps the most widely used programming construct. In C, we encounter three types of loops, which are:

- The for loop

- The while loop

- The do… while loop

Each of these loops will be taken up one-by-one, beginning with the for loop, in this tutorial.

The for loop

The for loop is perhaps the most widely used loop across all the programming languages. The general form of the for loop in C is as under.

for (initialisation;condition;updation) { do this; and this; and this too; }

Usually the for loop is controlled by a loop variable. If you are not understanding what I am trying to say, it’s fine, just bear with me and it will unfold itself very soon. The first part is the initialization part where we initialize the loop variable. Next part is the condition, where we check if we want to run the loop any further or not. If this condition evaluates to false, the loop is over. Finally, we have the updation, where we update the loop variable. Sounds gibberish? I hope this will make some sense soon enough. We’ll take an example of the natural number printing program, which prints all the natural numbers upto n, where n is provided by the user.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i;

for (i=1;i<=10;i++) {

printf("%d\n", i);

}

return 0;

}

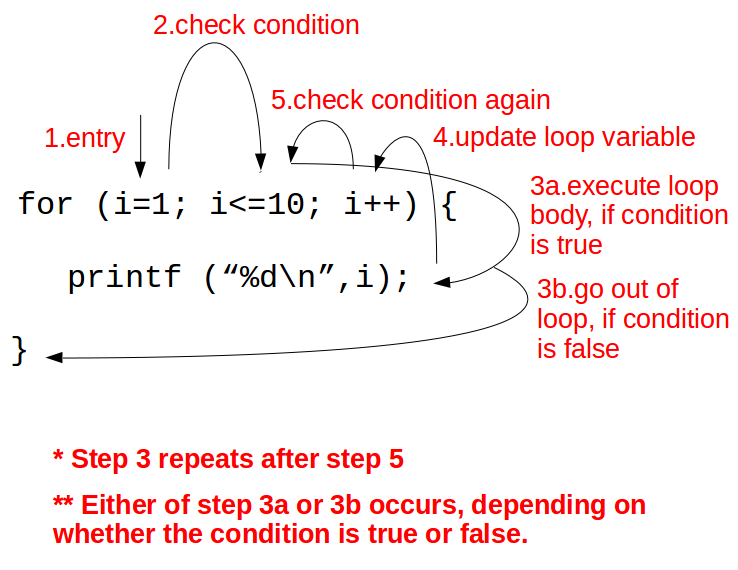

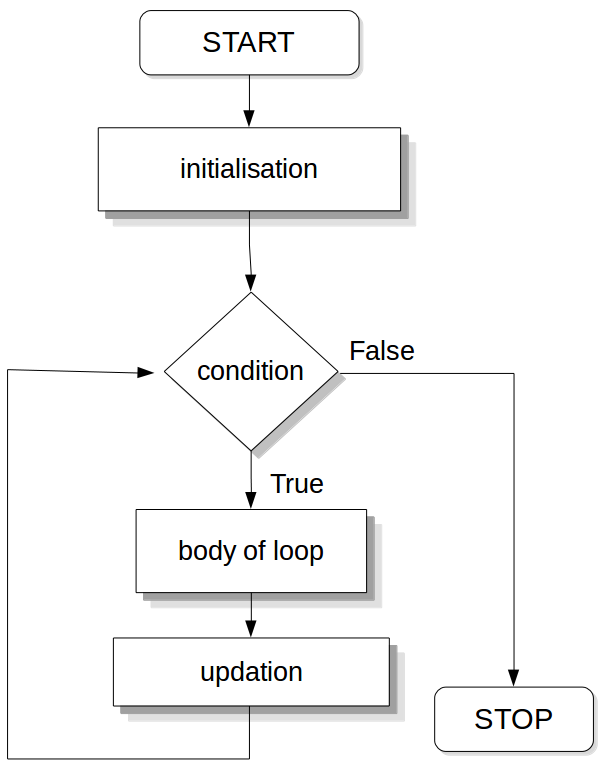

Simple, precise and elegant! It solves all our problems. But how exactly does it run? We’ll try to understand that in a while. We can see that i=1 is the initialisation statement, i<=10 is the condition statement and i++ is the updation statement. The loop begins at the initialisation statement. At first, i is assigned the value 1. Then the condition i<=10 is checked. Since it is true, the control enters the loop body and the value 1 is printed. Then the control moves to the updation part and the value of i is incremented to 2. The condition is checked and the value 2 is printed since the condition is true. This happens till the value of i is 10 and 10 is printed. After printing 10, the value of i becomes 11 and the condition is then checked, which evaluates to false, thus taking the control out of the loop. The whole working of the for loop can be visualized like this.

A flowchart will perhaps better clarify things because it is important to understand the sequence in which the loop works.

It is important to note that we can omit any or all of the initialisation, condition and updation statements and place it differently to give rise to different forms of the for loop. But for that we need to know about two keywords, extensively used with loop, the break and continue statements.

The break statement

The break statement allows us to come out of the loop instantly. Whenever a break statement is encountered, the control passes directly to the first statement after the loop. For example, look at the following piece of code.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i;

for (i=1;i<=10;i++) {

printf("%d ", i);

if (i == 5)

break;

}

return 0;

}

The output of the above program is 1 2 3 4 5. This is because after the value of i is incremented to 5, it is first printed and then the condition of the if statement is checked and found to be true and hence we encounter, the break statement. Break tells the loop, “You are done, man! Your time is over!” and the humble loop obliges. The control directly goes to return 0 statement on line 9. Though not comprehendible now, this break statement has immense uses, which we will see while programming.

The continue statement

With continue statement, the control goes to the loop updation. Whenever the continue statement is encountered, anything written after that in the loop body will be ignored and the loop counter will be updated. Let’s look at the following piece of code to understand it better.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i;

for (i=1;i<=10;i++) {

if (i>5)

continue;

printf ("%d ", i);

}

return 0;

}

The output of this program is again 1 2 3 4 5, but for different reasons this time. When i is less than or equal to 5, the condition of the if statement remains false and we just print the value of I. But when value of i becomes 6, the condition becomes true and we encounter the continue statement this time, which simply means all the lines of the loop body following it will be ignored. The value of i is again incremented in the next iteration and since the condition i>5 is still true, we encounter the continue statement once again and again all lines beneath that are ignored. This happens everytime until the loop ends.

Hope you have had a good understanding of the break and continue statements. Now, we can have a look at the different forms in which a valid for loop can be written.

Different incarnations of the for loop!

All the forms of for loop written below will give the same output. Can you figure out what that output will be?

- No initialisation in the for statement

i=1; for (;i<=10;i++) { printf("%d ", i); } - No condition in the for statement

for (i=1;;i++) { printf("%d ", i); if (i==10) break; } - No updation in the for statement

for (i=1;i<=10;) { printf("%d ", i); i++; }Or,

for (i=1;i<=10;) { printf("%d ", i++); }Or,

for (i=1;i++<=10;) { printf("%d ", i); } - Empty for statement!

i=1; for (;;) { printf ("%d ", i++); if (i==10) break; }

There can be many more similar variations in this way, but you get the idea, right!?

Multiple expressions in the for loop statement

- The initialisation expression in the for loop can contain more than one statement, separated by a comma. For example,

for (i=1,j=2;j<=5;j++) - There also can be multiple comma-separated updation statements. For example,

for (i=1,j=2;j<=5;i++,j++) - But there can be only one conditional statement, but it may be joined using logical operators. For example,

for (i=1;j<=5 && i<=8;i++)

A few subtle issues!

- When there is only one statement in the body of the for loop, the pair of braces may be skipped, as we did in if-else.

- The updation statement can not only contain increment operator, but also decrement or assignment operators. Hence, the following for loops are perfectly valid.

for (i=10;i>=5;i--) printf("%d", i); for (i=1;i<=10;i+=2) printf("%d", i); for (i=32;i>=1;i/=2) printf("%d", i); - In fact, it is interesting to note that the initialisation, condition and the updation part of a for loop can be replaced by any valid expression. Thus the following for loops are perfectly fine.

for (i=10;i;i--) printf("%d ", i); for (i=1;i<=10;printf("%d ", i++)); for (i=1;i<=10;i+=2) printf("%d ", i); for (i=1;scanf("%d", &i) && i;i--) printf("%d ", i); - Look at the following piece of code.

for (i=1;i<=10;i++); printf("%d ", i);What do you think the output of this code will be? It will be 11. Surprised? Well, see that there is a semi-colon right after the for loop statement and note that in earlier programs we did not use a semi-colon after the for loop statement. We are not supposed to use semi-colon just after the for loop. In that case, the above program looks like

for (i=1;i<=10;i++) ; printf("%d ", i);Simply, the loop runs from 1 through 10 and when i becomes 11, it comes out of the loop and executes the next line, i.e., printing the value of i, which is 11, and hence the output. So, remember this, you don’t wanna put a semi-colon after the for loop statement by mistake!

- A common mistake is not using the proper updation statement. For example, look at the following code

for (i=10;i>=0;i++) printf("%d ", i);Everything looks well and good, except for one thing. We start from i=10 and keep on increasing the value of i till it is greater than or equal to 0. Wait, what???!! If we are increasing the value of i from 10, it’s always going to be more than 0. So the loop is never going to end! This is an indefinite loop and it is a logical error. Beware!

Nesting of loops

Onto some nesting now! I hope you are familiar with the idea of nesting by now (if you’ve carefully read the previous tutorial). Now we’ll explore the concept of nesting with loops, i.e., we’ll use one loop within another! Don’t get scared just now. Just take a look at the following piece of code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i, j;

for (i=1;i<=2;i++) {

for (j=1;j<=2;j++) {

printf("%d + %d = %d\n", i, j, i+j);

}

printf("%d - %d = %d\n", j, i, j-i);

}

return 0;

}

We get the following output for the above program.

1 + 1 = 2 1 + 2 = 3 3 - 1 = 2 2 + 1 = 3 2 + 2 = 4 3 - 2 = 1

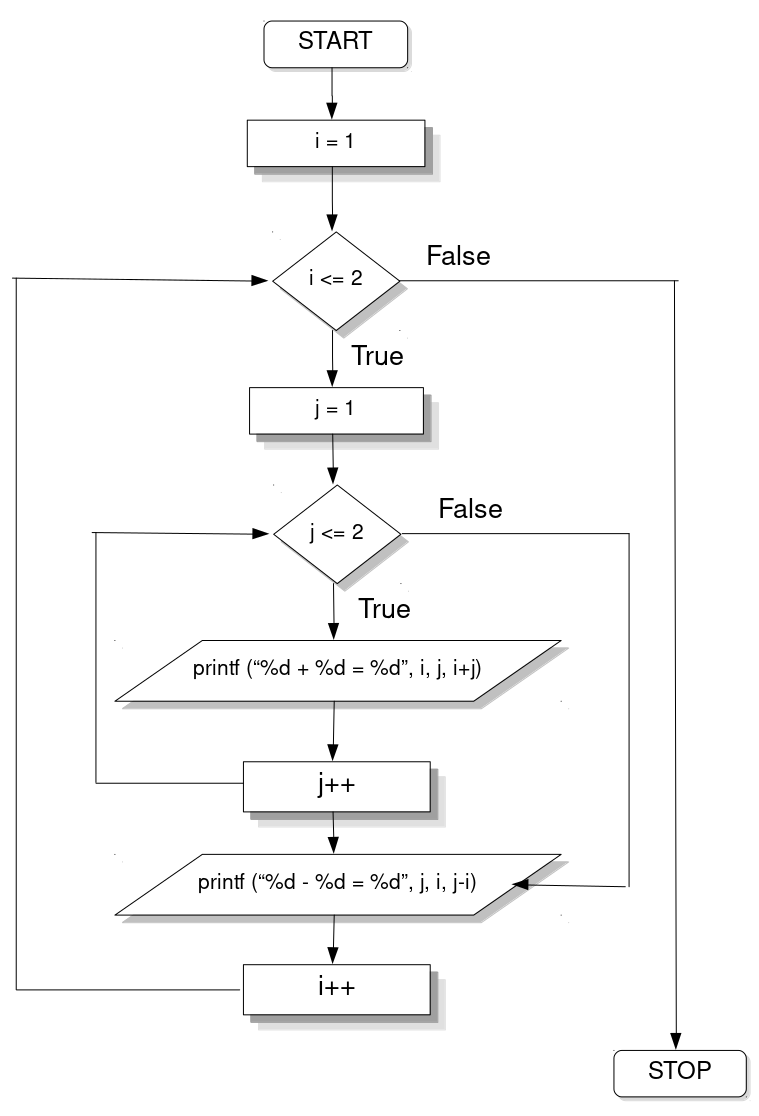

I guess some explanation is due now. Let’s understand the working of the code. After the declaration of i and j, the compiler encounters the first for loop statement. i is initialized to 1, the condition i<=2 is found to be true and hence, the control moves into the body of the outer loop and the compiler encounters another for loop statement. This time j is initialized to 1 and the condition j<=2 is also found to be true. Now the control moves on to the printf() statement and the line 1 + 1 = 2 is printed. Now a question arises that where the control should go next. If you look at the working of the for loop again, you’ll find that after the loop body is executed the control goes to updation. But there are two updations: i++ and j++. Which one is to be performed? Or both, maybe? The answer is that only the updation part of the immediately preceding for loop is executed, i.e., j++ and then the condition j<=2 is checked. After printing the line 1 + 2 = 3, j becomes 3 and since the condition of the inner for loop does not satisfy anymore, the control comes out of the inner for loop and moves on with the body of the outer for loop. The printf() statement on line 7 is executed giving the output 3 - 1 = 2, since the value of j is 3 now. After being done with the loop body of the outer for loop, i is now incremented to 2 and the inner loop works all over again to generate the remainder of the output. The control reaches to return 0 when i becomes 3. The whole process can be summarized with the following flowchart.

Look at the flowchart. Try to understand it carefully. This will probably clear up things. As is the case with nesting of ifs, nesting of loops can also be done upto any level! It may seem now that nesting of loops is a very tough concept or that it’s not very useful, but trust me, once you get the idea of it, it is going to be very easy to understand and implement and it is super useful in many cases. So much so, that there is no other way around it!

The goto statement

The goto statement in C provides an unconditional jump from one line of code to another i.e., it alters the control flow of the program. The syntax of goto statement is given as follows.

gotolabel; . .. ...label: statement;

By the syntax, it can be easily understood how the goto statement works. By using goto, we just tell the compiler to move the control to some line which we have already named using a label. Label can be any plain text (except a C keyword) and it can be set anywhere in the C program above or below to goto statement. It is just the name for a particular line. An example will make the use of goto clearer.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i = 2, j = 3;

goto xyz;

i = i + j;

printf("%d\n", i);

xyz: printf("%d\n", i);

return 0;

}

The output for the above program is 2, which must be self-explanatory. The 3rd and the 4th lines of the main() function never gets executed. As soon as goto is encountered in the 2nd line, the control jumps to the 5th line with the label xyz and the printf() statement is executed generating the output 2. This was a really simple example. Let’s look at a complicated one.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i = 1, s = 0;

sum: s += i;

if (++i <= 5)

goto sum;

printf("%d\n", s);

return 0;

}

Can you figure out the output of the above program on your own? Let me give out a hint. The above program uses goto as a replacement for looping.

Seemingly useful, the use of goto is highly discouraged my many experts, the reason being goto makes the program obscure and it becomes a real challenge to trace the control flow of the program. This makes the program hard to understand and harder to debug or modify. Any program that uses a goto can be rewritten to avoid them.

The only good use of goto is perhaps breaking out from nested loops, because break is only helpful to break out from the innermost loop in which it is used and the execution starts from the next line of code after the block. Look at the following demonstration. We want to break from both the loops when i becomes 2.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i, j;

for (i=1;i<5;i++) {

for (j=1;j<=2;j++) {

if (i == 2)

break;

printf ("%d ", i*j);

}

}

return 0;

}

If you run the above program, you’ll get the output as 1 2 3 6 4 8. The execution comes to an end only when the condition i<5 becomes false, which is not what we wanted. This is because when i becomes 2 and the break statement is encountered, control only comes out from the innermost loop. But i keeps on getting incremented till it does not become 5, which explains the reason for this output. goto is our way out from this problem. Check out the following code to understand how.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i, j;

for (i=1;i<5;i++) {

for (j=1;j<=2;j++) {

if (i == 2)

goto end;

printf ("%d ", i*j);

}

}

end: return 0;

}

See how goto helped us achieve what we wanted. Now since I said every program using goto can be written without using it, it becomes neccessary to show to you folks how the above solution can be achieved without using goto. So here it is!

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int i, j, f = 0;

for (i=1;i<5 && f!=1;i++) {

for (j=1;j<=2;j++) {

if (i == 2)

f = 1;

printf ("%d ", i*j);

}

}

return 0;

}

Okay! So this has been a really long tutorial. I’d like to put an end to this one right here. The next one will bring to you the other two forms of loops used in C and there’s a lot more programming to come! Hope you got know a few things from this one. So, keep reading and keep coding! Adios!