We covered the whole of integers but integers are not the only numbers that we need to store in a computer. There are real numbers with decimal points (also called radix point). They are called floating-point numbers in C (or any other programming language for that matter), for reasons explained a bit later. These floating point numbers can be written in 2 ways in C – Fractional form or Exponential form. Let’s first learn how to write floating point numbers in these two forms.

Fractional form

The fractional form maybe used when the number to be represented is not very large or very small. We use this form of representation in our normal arithmetic. Following are the features of wrting a floating-point number in this form:

- A floating-point number must have at least one digit.

- There may or may not be a decimal point (radix point). If there is no decimal point, it is considered to be after the least significant bit i.e., the rightmost digit.

- It may be positive or negative. Default sign is positive.

- No commas or blanks are allowed within a floating-point number.

For example: +432.34, 426, -32.67, etc.

Binary representation of real numbers in fractional form

Of course, there is binary! Let’s see how to get the binary representation of a real number which is in fractional form.

Let’s take an example, say 16.625. We know how to convert the portion on the left of the radix point into binary form. In this case, 16 would convert to 10000.

(16)10 = 1x24 + 0x23 + 0x22 + 0x21 + 0x20

Now we are only left with 0.625. For the portion after decimal, we follow the following method:

- Multiply it by 2 and keep the number to the left of the decimal as a binary digit.

- Multiply the remaining portion i.e., the portion after the radix point by 2 and do the same. We have to keep doing it till we get to 0 on the right hand side of the radix point.

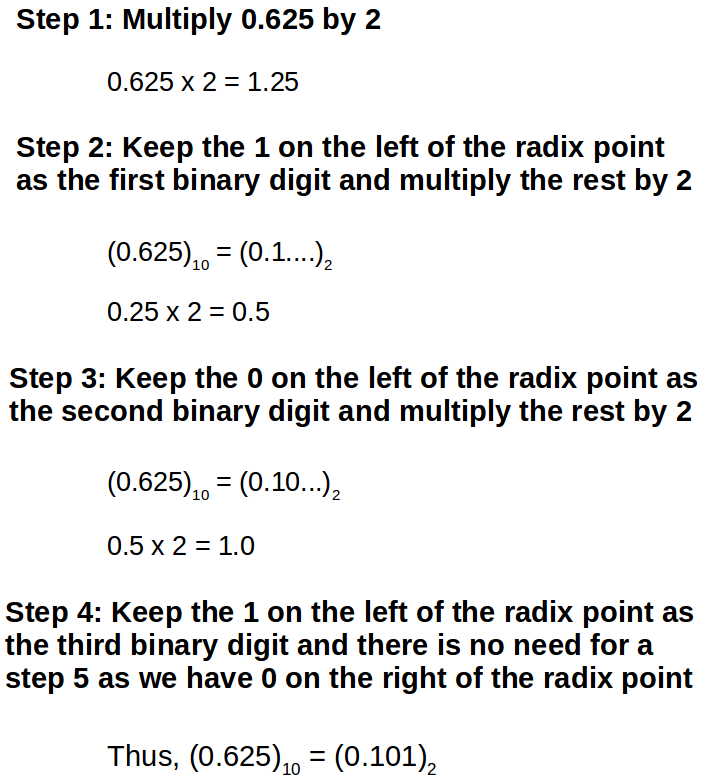

The following graphic illustrates this method with an example of the task at our hand i.e., 0.625.

This can be verified if we try to see that

(0.101)2 = 1x2-1 + 0x2-2 + 1x2-3 = 0.5 + 0 + 0.125 = (0.625)10

Thus, we can write (16.625)10 = (10000.101)2. This is all well and good but what if we try to convert decimal 0.1 or 0.33 to binary form? We’ll keep on multiplying by 2 infinitely but we’ll not reach the end. But we have limited space on a computer. In such cases the solution is rounding up. We’ll see how to do that.

Rounding to nearest or even in binary

We are all familiar with rounding numbers in decimal for. Rounding numbers in binary is similar. We just have to follow the simple rules given below.

- We should round to the number for which we get the least error.

- In case of a tie, we should choose the number with the least significant bit 0 (i.e., even).

Let’s try to convert (0.33)10. Suppose we have only 5 bits to store the number after the radix point. Let’s see how we can perform the rounding.

We can see that (0.33)10 = (0.0101010…)2. When we try to round it to 5 bits, we first check:

0.0101010 – 0.01010 = 0.0000010 and

0.0101010 – 0.01011 = –0.0000010

This is a tie! So, we choose 0.01010 as our answer as the LSB is 0. The subtraction can be peformed just as we did in integers. Treat the numbers as integers, convert the negative number to two’s complement and add them.

After learning the fractional form of representation of real numbers, let’s look at the second method of representation, the exponential form.

Exponential form

The exponential form is usually used when the value of the number to be represented is either too large or too small. However, C does not restrict us in any way from using either of the two forms of representation. In exponential form, the number is represented in two parts with an e or E in between. The part appearing before e is called mantissa or significand, whereas the part after the e is called exponent. Thus 0.000543 in fractional form maybe written as 5.43e-4 (which means 5.43x10-4 in normal arithmetic). Here, 5.43 is the mantissa and -4 is the exponent. This a more scientific form of notation. Computers use this form to store floating point numbers (we’ll discuss that in a while). Following rules must be observed while writing real numbers in exponential form:

- The mantissa part and the exponent part should be separated by a letter e or E.

- The mantissa part may have a positive or negative sign. Default sign is positive.

- The exponent must have at least one digit which must be a positive or negative integer. Default sign is positive.

- No commas or blanks are allowed.

For example: +3.2e-4, -0.2E3, -32.67e8, etc.

Floating-point and fixed-point numbers

When the number of bits on the left and right hand side of the radix point of a real number is fixed, it is called fixed-point number. Using this form of representation of binary numbers has a demerit – we will not be able to store numbers that are either too small or too large. Let’s say we have four bits on each side of the radix point. So, we store the number 16.275 as 0016.2750. This is fixed point representation of real numbers. We can also express the number (16.275)10 as 1.6275x101 or 16275x10-3 or 0.16275x102. Let’s consider 1.6275x101. Here 1.6275 is the mantissa, 1 is the exponent and 10 is the base. See how the point is floating. It is not fixed. So this mantissa-exponent form of representation of real numbers is called floating-point representation. Using this representation, we can store even too large or small numbers which was not possible with fixed point representation. Computers make use of this form of representation to store real numbers. Hence, real numbers are stored as floating-point data type. Floating-point is also applicable on binary. For example, (101.0101)2 can be represented as 0.1010101x23 or 1.010101x22 or 1010101x2-4. Notice the change of base here. Earlier we were using decimal numbers so the base was 10. Now in binary the base is 2.

Normalized form of binary real numbers

We have seen that in floating point form of representation that we can have any number of digits before the radix point in the mantissa by changing the exponent. Let’s take the example of binary 101.0101. When we express the number in such a way that the first digit is non-zero and there is only one digit before the radix point i.e., 1.010101x22, it is said to be in normal form. Since in binary form, the only non-zero digit we have is 1, hence it is implied that in normalized form there will be a 1 before the radix without our explicitly saying so. This fact is going to be very useful in a while.

Implementation of floating point numbers

Now we are ready to jump right into the details of the implementation of floating point numbers in memory of a computer. This implementation follows a worldwide standard called the IEEE-754 standard. According to this standard, a floating point number has 3 important parts – a sign bit, a biased exponent and the mantissa. A float is usually allocated 32 bits, out of which one is the sign-bit, 8 bits are for the exponent and remaining 23 bits are for the mantissa.

- Sign bit: This is as simple as it gets. The sign bit is 0 for positive and 1 for negative.

- Biased exponent: Why biased? Because we add a “bias” to the exponent and then store it. With a 32-bit float, this bias is 127 and with 64-bit long float (called double), it is 1023. We’ll discuss why this biasing is done in a while.

- Mantissa: We have already seen that in the normalized representation a mantissa has an implied 1 before the radix point, so there is no need to store the 1. The 23 bits allotted for mantissa can all be used to store the bits after the radix point, thus giving one extra bit for “free”.

Let’s consider the decimal number 62.5 x 10-2. To see how this number will be stored into memory, we have to first consider the binary conversion of 0.625 which will be 0.101 or 1.01x2-1 in normal form. According to the scheme we discussed above, these number will be stored as follows:

62.5 x 10-2 = 0 01111110 01000000000000000000000

Here the first bit is 0, which is the sign bit signifying positive number. The next 8 bits translate to 126 in decimal. Since the exponent is -1, after adding the bias of 127, we get 126. The final 23 bits are the 23 bits after the radix point in the mantissa.

Why biasing?

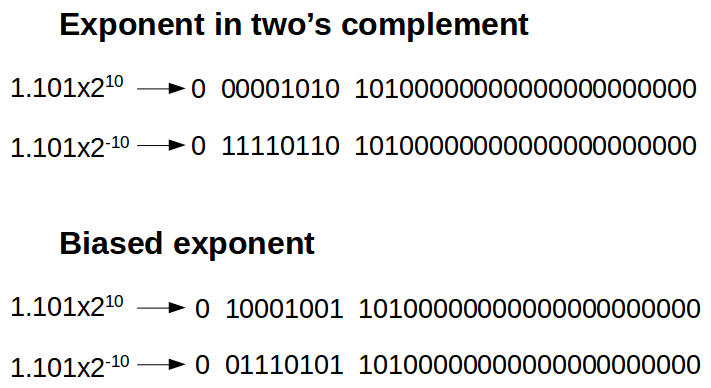

Let’s consider two binary real numbers: 1.101 x 210 and 1.101 x 2-10. Let’s see what happens when we store the exponents in biased exponent form and in two’s complement form.

Notice that in biased exponent form, we can lexicographically compare the two numbers (i.e., compare bit-by-bit) and the number with the negative exponent looks smaller but in two’s complement form see that lexicographic comparison has no meaning since the negative exponent looks bigger. For this reason, IEEE-754 specifies that the exponent be biased.

Special numbers and non-numbers

IEEE-754 standard reserves some bit patterns for some special numbers which are listed as follows:

- Zero: Zero is represented with all 0’s in exponent and mantissa bits. But the sign bit can be 0 or 1 denoting +0 or -0. This may seem useless but this has some practical uses. When two very close numbers are subtracted, the result may not be exactly 0 but very close to 0. In that case, when we do the subtraction the sign remains preserved and we can tell which number was greater.

-

Denormalized numbers: In the scheme of representation described above, we were using normalized form of representation, meaning we were implicitly assuming there is a 1 before the radix. The minimum number we can represent in this way is 1.00000000000000000000000x2-126 (or 2-126). See that if the exponent was -127, we would have ended up having 0 at all bits of the exponent and also we have 0’s at all mantissa bits. But 0 at all places represent 0. So -126 will be the least exponent we can represent using normalized form.

What happens when the number is still smaller? Do we not store that? This situation is called underflow. If we cannot store that we’ll have sudden loss of data. I mean if we try to subtract numbers the difference between which is smaller than the smallest possible number we can represent using nomalized form, we will need to store 0 and the result won’t be very accurate.

That is why, when we reach this point, we let go of our assumption that the leading bit is 1. To reduce the loss of data when an underflow occurs, IEEE-754 includes the ability to represent fractions smaller than are possible in the normalized representation, by making the implicit leading digit a 0. Such numbers are called denormalized or denormal numbers. They don’t include as many significant as a normalized number, but they slow down the loss of data when the result of an arithmetic operation is not exactly zero but is too close to zero to be represented by a normalized number.

A denormal number is represented with a biased exponent of all 0 bits, which represents an exponent of −126 in 32-bit float (and not −127), or −1022 in 64-bit double (and not −1023) and a non-zero mantissa field. In contrast, the smallest biased exponent representing a normal number is 1. Perhaps a few examples will clear the whole thing.

Notice the loss of precision i.e., significant digits. In the smallest normalized number, we have 24 significant digits, whereas in the largest denormalized number there are 23 significant digits and by the time we reach the smallest denormalized number, we are left with only 1 significant digit. But this is a gradual loss. This is desirable. This prevents the sudden loss of precision as well as increases the range.

| Type | Sign | Actual exponent | Biased exponent | Exponent field | Significand (fraction field) | Value |

| Zero | 0 | -127 | 0 | 0000 0000 | 000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 | 0.0 |

| Negative zero | 1 | -127 | 0 | 0000 0000 | 000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 | -0.0 |

| Smallest normalized number | 0 or 1 | -126 | 1 | 0000 0001 | 000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 | ±2-126 ≈ ±1.18x10-38 |

| Largest normalized number | 0 or 1 | 127 | 254 | 1111 1110 | 111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 | ±(2-2-23 )x2127 ≈ ±3.4x1038 |

| Smallest denormalized number | 0 or 1 | -126 | 0 | 0000 0000 | 000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0001 | ±2-23 x2-126 ≈ ±1.4x10-45 |

| Largest denormalized number | 0 or 1 | -126 | 0 | 0000 0000 | 111 1111 1111 1111 1111 1111 | ±(1-2-23 )x2-126 ≈ ±1.18x10-38 |

- Infinities: IEEE-754 also lays down provisions for representing two infinities, +INF and -INF. The bit pattern is as follows:

Sign bit: 0 or 1, denoting positive or negative infinity

Biased exponent: All 1 bits

Mantissa: All 0’s - Not a Number or NaN: Some operations of floating point arithmetic are invalid, such as taking the square root of a negative number. The act of reaching an invalid result is called a floating-point exception. Such a result is represented by a special code called a NaN, for “Not a Number”. All NaNs in IEEE-754 have this format:

Sign bit: either 0 or 1

Biased exponent: All 1 bits

Mantissa: Anything except all 0 bits

Modifiers with floating-point numbers

We cannot use the short and signed/unsigned modifiers with float. As mentioned earlier, long float is called double and long long float is called long double. The sizes and ranges of these are given in the following table.

| Data type | 16-bit compiler | 32-bit compiler | ||

| Size (in bytes) | Range | Size (in bytes) | Range | |

| float | 4 | 1.175494E-38 to 3.402823E+38 | 4 | 1.175494E-38 to 3.402823E+38 |

| double | 8 | 2.225074E-308 to 1.797693E+308 | 8 | 2.225074E-308 to 1.797693E+308 |

| long double | 10 | 1.000000E-4932 to 1.189731E+4932 | 16 | 3.3621E-4932 to 1.18973E+4932 |

The range given here is on the positive side. It is symmetric on the negative side. You can check the size and range of these modified data types on your compiler by running the following piece of code.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <float.h>

int main () {

printf ("Size of float is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (float));

printf ("Range of float is from %e to %e\n", FLT_MIN, FLT_MAX);

printf ("Size of double is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (double));

printf ("Range of double is from %e to %e\n", DBL_MIN, DBL_MAX);

printf ("Size of long double is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (long double));

printf ("Range of long double is from %Le to %Le\n", LDBL_MIN, LDBL_MAX);

return 0;

}

I think we now have a quite good understanding of how floating-point numbers are stored in memory. I think this was a tough one. It may take some time to digest. Read it twice or thrice if you don’t understand it the first time and play with these values on your copies to get a better understanding. The next one will be on the last basic data type, the character data type. Get your head around this one till the next one comes. Stay tuned!