If I recall correctly, we are due with octal and hexa-decimal integers and floating-point numbers. So, here we begin without any further ado.

Octal Integers

- Octal integers are base 8 numbers i.e., they consist of digits 0 through 7.

- In C, we can write octal numbers by writing a 0 before the number. For example: 023 means (23)8 to the compiler.

- How are they stored in memory? In the same way decimal numbers are. They are converted into equivalent binary numbers and then stored. Let’s see how to do that. We’ll learn two methods. The long one and then of course, there is a short one.

Octal to binary via decimal

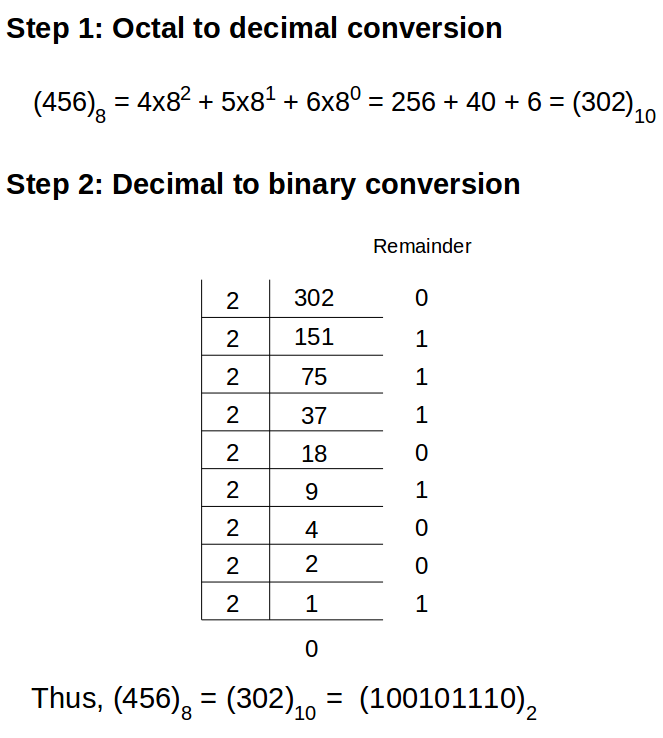

To convert an octal number into decimal, we use the same method we used to convert binary numbers to decimal numbers but we use 8 instead of 2 since octal is base 8. Then we’ll convert the decimal number into binary and we know how to do that.

Let’s take an example of (456)8.

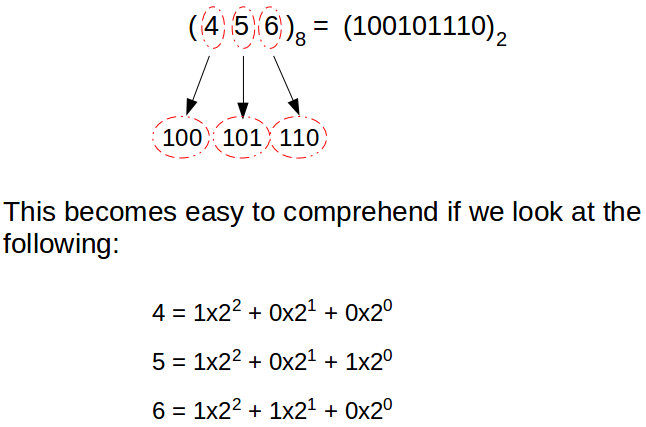

Octal to binary directly

Take each digit of octal number and use three binary digits to represent each digit. Sounds confusing? Perhaps an example will make it clear.

Looking at the previous result it is evident that this procedure also yields the correct result. Now let’s try to do the reverse conversion.

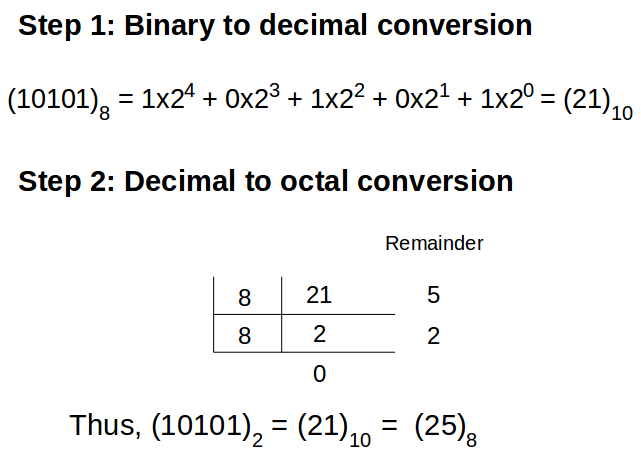

Binary to octal via decimal

We already know how to convert a binary number into decimal form. To get the octal number from its equivalent decimal form, we just follow the procedure we use to get binary number from decimal numbers. Following graphic illustrates the whole method.

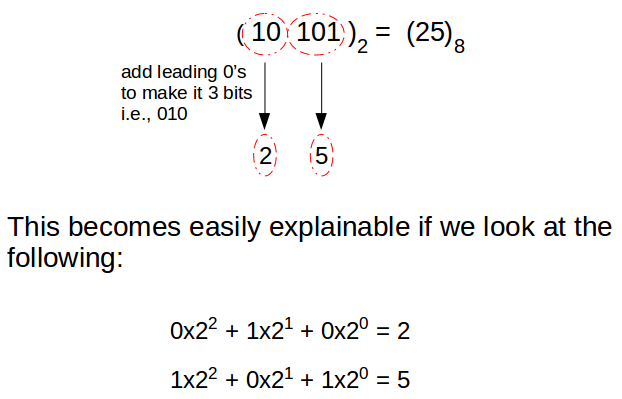

Binary to octal directly

We’ll do the reverse of the process we did for converting octal to binary directly, that is, take three digits at a time from the right and use them to represent one octal digit on the right till all digits are exhausted. The process will become clear enough once we take an example.

I think we are quite done with octal integers. Let’s move on to hexa-decimal integers.

Hexa-decimal Integers

- Hexa-decimal integers are base 16 numbers i.e., they consist of digits 0 through 9 and A through F, where A represents 10 and F represents 15.

- In C, we can write hexa-decimal numbers by writing a 0x before the number. For example: 0x47A means (47A)16 to the compiler.

- By now you would have guessed that hexa-decimal numbers are also converted into equivalent binary numbers and then stored and also what are we going to do next. So let’s jump right into the act and learn the two methods to convert hexa-decimal numbers into binary form and also its reverse counterpart.

Hexa-decimal to binary

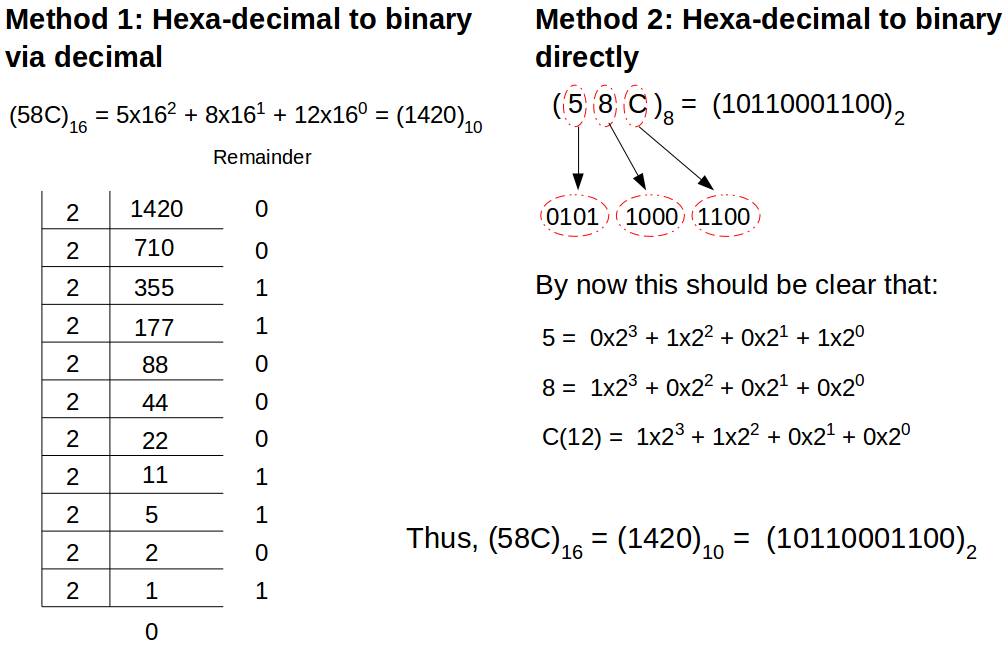

The process of conversion remains the same for the longer method, we just need to make a small change and as you can probably guess the change is that we need to use 16 in place of 8 as the number is in base 16. In the short-cut method however, the change is that 1 hexa-decimal digit converts to 4 bits of binary in place of 3 in octal.

Let’s take an example of (58C)16. The following illustration gives a clear insight into both the methods.

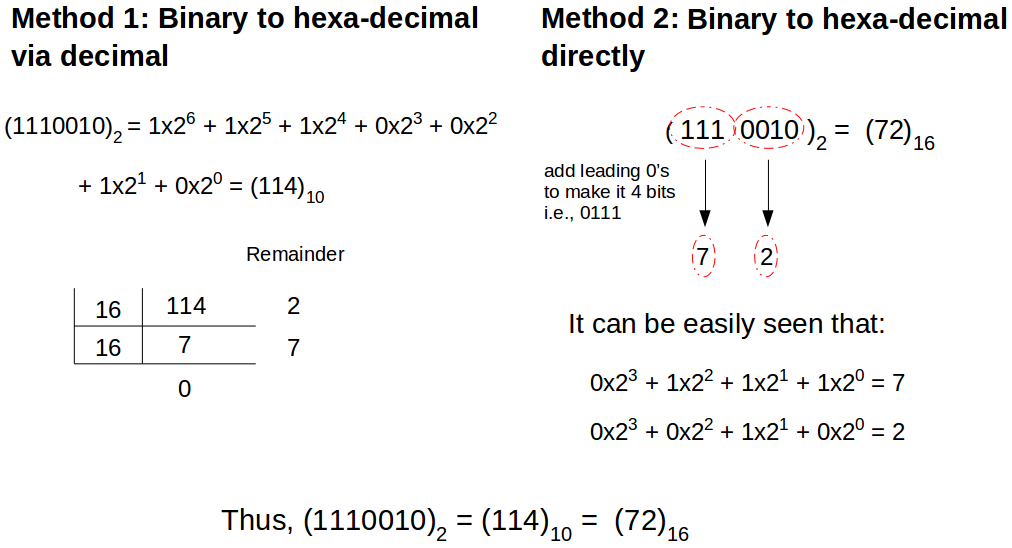

Binary to hexa-decimal

I would urge you to try the reverse process on your own and then see the following illustration which explains both the long and the short method.

We’ve have had enough of number conversion. We’ll take up modifiers next and see how these change the properties of the basic integer data type.

Modifiers

Modifiers can be defined as keywords used to change the properties of the data type with which it is used. In C, we encounter 5 modifiers which can all be used with “int” data type.

- Long: The ‘long’ modifier can be used with int to increase the size of int and consequently the range also increases.

- Long long: This modifier further may increase the size of an “int” data type.

- Short: Generally “int” data type has different sizes on different compilers. The “short” keyword can be used with integer data type to explicitly allow an “int” to be of only 2 bytes. As a result, working with it becomes faster. When we know our number is not going to be more than what “short int” can store we can use it to make our program faster. The difference is more prominent in long programs.

- Signed: Default type of “int” is signed. It means 1 bit of the integer is going to store the sign of the number. As a result we can store both negative and positive integers.

- Unsigned: When an integer is declared as unsigned, we are telling the compiler that we are going to work with only positive numbers and as such there is no need to allot 1 bit as the sign bit. As a consequence, the range on the positive side increases as we are getting one extra bit for storing the values. So when we are going to work with positive numbers only, using unsigned modifier can help us to increase the range of our variable.

In C, not always does the modifier modify the size and range of the data type. What we are sure of though is that

sizeof (short) <= sizeof (int) <= sizeof (long) <= sizeof (long long)

Notice the sign. It’s an less than or equal to, implying there may or may not be a change. The following table gives the size and range of int used with the modifiers:

| Modifiers used with | 16-bit compiler | 32-bit compiler | ||

| Size (in bytes) | Range | Size (in bytes) | Range | |

| short int (signed short int) | 2 | -215 to 215-1 | 2 | -215 to 215-1 |

| unsigned short int | 2 | 0 to 216-1 | 2 | 0 to 216-1 |

| int (signed int) | 2 | -215 to 215-1 | 4 | -231 to 231-1 |

| unsigned int | 2 | 0 to 216-1 | 4 | 0 to 232-1 |

| long int (signed long int) | 4 | -231 to 231-1 | 8 | -263 to 263-1 |

| unsigned long int | 4 | 0 to 232-1 | 8 | 0 to 264-1 |

| long long int (signed long long int) | 4 | -231 to 231-1 | 8 | -263 to 263-1 |

| unsigned long long int | 4 | 0 to 232-1 | 8 | 0 to 264-1 |

As you can see we can use signed/unsigned modifier in combination with short/long/long long. The sizes and ranges of int coupled with its modifiers vary from machine to machine and compiler to compiler. The above data has been recorded with a GCC (32-bit) and TurboC/C++ (16-bit). Your compiler may or may not report different sizes. To know the sizes of these modified integers you can run the following piece of code on your computer.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <limits.h>

int main () {

printf ("Size of short is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (short));

printf ("Range of short is from %d to %d\n", SHRT_MIN, SHRT_MAX);

printf ("Maximum unsigned short is %hu\n\n", USHRT_MAX);

printf ("Size of int is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (int));

printf ("Range of int is from %d to %d\n", INT_MIN, INT_MAX);

printf ("Maximum unsigned int is %u\n\n", UINT_MAX);

printf ("Size of long is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (long));

printf ("Range of long is from %ld to %ld\n", LONG_MIN, LONG_MAX);

printf ("Maximum unsigned long is %lu\n\n", ULONG_MAX);

printf ("Size of long long is %ld bytes\n", sizeof (long long));

return 0;

}

You can declare variables of integer type with modifiers in two ways:

- Write int explicitly: This method is a must while using signed/unsigned modifiers but not for short/long/long long modifiers. For example: unsigned int a, long int b, unsigned long int c, etc.

- Without explicitly writing int: You can also omit the int keyword. Compiler automatically interprets that you are talking about integers. You can use this method with only short/long/long long modifiers. For example: long a, short b, unsigned short c, etc.

With this much said, I would like to bid adieu for now. The next one is on floating-point data type. You people will notice that till now we still are going through so much of theoretical aspects of C and not a bit of programming. If you are getting frustrated, don’t. Even I would like to get to the programming part as soon as possible. But I can promise you this is necessary, not just for examination purpose (yes, this is all included in the syllabus!) but also for the understanding of how everything happens around in C. We have a little more theory left, and after that we will move on to the best part, programming! So, stay tuned.